BOOK EXCERPTS

Shadows of the Ivory: Book Excerpts

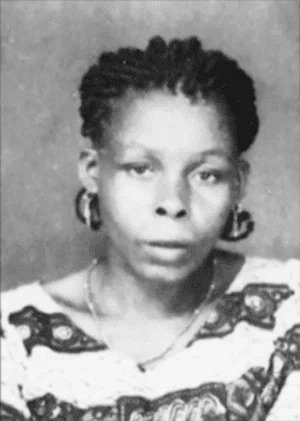

Therese Yei Meledje appeared in my dreams at first she was nameless, a shadow.

I created everything about my mother, the mother who gave birth to me; a creation I built from imagination with only one reference point: me—or whoever I saw in the mirror’s reflection.

I forgot the negritude because I did not even know it existed; my dreams did not know either. In my recurrent reverie, my mother lost the most precious attribute she possessed: her blackness. Once I left Cote D’Ivoire, I grew up in a white world where mouths veiled the truth.

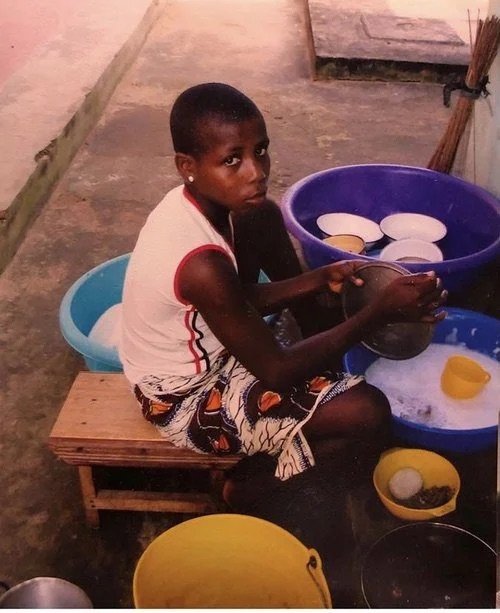

I was a child, a bi-racial little girl snatched from her African roots. In some ways the separation was a blessing—I survived—but beyond my brownish skin lived a past I muted until I no longer could bear the lie.

I remained open to my African family’s folklore, no matter its accuracy; my eagerness to learn about my past transcended the limits of its truthfulness.

Baobabs can live for thousand years and I thought my mother could too. The tree is also known as “Tree of life” and when I hug trees in nature, at many occasions, I hug my mother and feel the years of absence.

My mother used to sway her hips and dance barefoot in the dirt. I learned that villagers circled Therese Yei Meledje while she danced free in the heart of her village (mine, too). I imagined my little body nestled inside her while she squatted in the fields and worked under the blazing sun in the unforgiving heat known to Africa; I suspected my presence inside her only made her hotter. My memories of my mother are sparse but I believe I have a legitimate reason to hate the heat.

I was able to perceive the murmur of her voice. Words sounded distant, covered by the underwater landscape I lived in. Perhaps she talked to me when she reached a point of exhaustion, standing in the fields cutting the crops, her face covered in sweat. She had long elegant hands. Did she use them to smooth the curve of her belly when I poked her with an elbow or a knee asking for attention?

Often, I traveled back, letting my mind wander to the time of the two of us. Scenes appeared, I just had to close my eyes.

We did not know when we would see each other again and our return home with the civil war’s violence was questionable. Delphine left my arms against her will when our sister Jeanne called her with insistence from a distance. The separation broke my heart, my soul, my guts.

Delphine kept turning around and waving, her face transformed by her pain. She let go of Jeanne’s hand and ran back toward me.“Maryline, reste avec nous, ne me laisse pas seule’’ (Maryline, stay with us, don’t leave me alone), she cried.

How could an eleven year old little girl understand? What else could I do? Powerless, I just cried with her. I knelt in front of her, “Delphine, I cannot stay outside the house for too long. Someone could report our presence in the village because Lydia is white, I’m mixed and we’re French. You don’t want the rebels to find us?’

She looked down.“Look at me, Delphine, it’s not what you want?’’ She turned her head from right to left.

“Alors, écoutes -moi… So listen, at the same time we are going to walk back. I’ll walk toward the house and you’ll catch up with Jeanne. You cannot look back—promise me.’’

She nodded; I kissed her with all the tenderness I had in me then started to walk toward the house without looking back. My hands tightened—strong fists holding the pain. My chest hurt from holding back the tears. I entered the kitchen, closed the door, slid down against it, my hands holding my face. I let everything go; a cascade of pain. What I did was cruel, I thought, but I had no choice.

The insults I received in my childhood about my negritude knocked me in the face—what did they see I could not see? I woke up, later in life, from the false reflection I kept on seeing in the same mirror; stung by my own indifference. To those who called me names, I must thank you.

Haters suffered in their own skin; yesterday, still today and will maybe continue to suffer tomorrow—there’s a fear to lose this feeling of superiority.

In their blinded eyes, my negritude meant weakness and low-grade intelligence. The minute I portrayed my humanness with a certain degree of intelligence, I became a threat; a threat of being superior to the white man—this is where the fear came from, and still comes from.

It is important to understand this : that my African mother was illiterate has nothing to do with a lack of intelligence, but has everything to do with fate.

My adoptive father was addicted to pornography. I was a romantic. In the language of love, we were strangers, even enemies. I wrote ‘was’ when I could have written in the present tense. At 90 years old, he is the same man, but the porn effect has deteriorated over the years—nothing works forever. Today, I am still a romantic; the heart is a strong muscle. Jacques, my adoptive father is a very polite man as far as greetings are concerned: ‘Bonjour Madame, Bonjour Monsieur, Bonjour Messieurs Dames’. In those instants I was listening, I was learning politeness—a rare inheritance he passed on to me. Still a child, I’d stop whatever I was doing to witness his authoritarian figure and his army haircut melt into a smile; allof a sudden he was someone else. My adoptive father never wished my birth day as if losing my biological mother and father was not enough. He seemed cut from the privilege to express love and care; perhaps a dysfunctional artery blocked his blood from reaching the heart.

Jacques’ answers were always ‘no’.

”Can I go to my friend’s house?”

‘No.”

”Can I hold the dog”

”No.”

”Can I sleep over?”

”No.”

”Why?”

”No.”

I stopped asking.

My adoptive mother, my best ally at home, walked the trenches for me, and served as a liaison during all this years of war between my adoptive father and I.

I still don’t know to this day how she negotiated a ‘yes’.

Couple years ago I traveled back to France. My adoptive mother had contracted the Horton disease and lost most of her sight. I stayed with my adoptive parents for 3 weeks in Brittany where they live now.

I remember a specific afternoon. Jacques slept a lot, part of the days and long nights as elderly often do. I entered his bedroom and said: “Debout mon général”(Get up my general).

He looked at me.

“Je suis fatigué” (I’m tired)

He always said that.

I grabbed a pillow and started a pillow fight. Here we could meet, at last. Old age brings you back to childhood. The lost child in me never left. For an instant while pillows flew across the room, I had a flashback to the time I hated him—the substitute father— I had stopped calling Dad for couple decades. A pillow landed in my head and shook the memory. He laughed like a kid who’s lost most of his teeth.

Forgiveness is all I had left. I had tried hate, indifference, pity—year after year— and it changed nothing except reinforcing the fact that I was fatherless.

My African mother’s funeral took place in Vieux-Badien, Côte D’Ivoire, on October 13, 2004, a week after I received the news of her passing. No flights were available on this date so I booked a flight departing a few weeks later. I thought about the funeral—a lot. It kept me awake at night. Being present on that day was beyond my capability.

I could not fathom the idea of standing close to my mother’s dead body after longing for her most of my life. Nine months in her womb, feeling her moves—all of them; listening to her breath and smelling the perfume of her skin was all I had. Nothing to add; it was final.

Facing my half- brother Atchori seemed like a bad idea. Although I knew the first person I should blame was myself—still, I was angry. Regrets are for those who missed an opportunity. If only I knew I had an opportunity. It would have been possible growing up. I just needed a little help, a little love. If the white world I lived in accepted and valued who I really was, perhaps I could have seen too; and mirrors would have stopped lying all those years. It was too late for unavailing remorse.

Fear was there all along and I don’t have a problem saying that I was scared. It was like losing ground and floating, until something snaps you down, bruises you, and wakes you with the pain.

William Shakespeare wrote: “When we are born, we cry that we are come to this great stage of fools.”

I wonder if when we die, we smile.

Below are two articles published on Mother’s Day in 2005 by The Charlotte Observer, narrating my experience during my first trip back to Ivory Coast. I left Ivory Coast when I was 1 year old and returned for the first time when I was 38 years old.